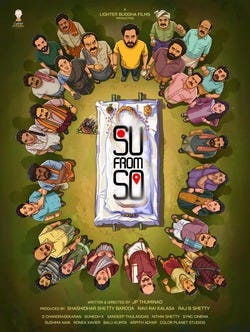

Su from So is a village comedy possessed by the spirit of a horror comedy. And it’s hauntingly funny.

The film opens with a “slice of life” in-the-village type of scene: our attention glides seamlessly from a funeral to a wedding, two settings that should be in contrast to each other but are not. What binds the two together are the food served on both occasions and the villagers shouting and teasing each other. Life is a cycle, sorrows and happiness in one constant, smooth transition.

Not for long, though! Soon, the village is terrorized by the ghost of a deceased woman, Sulochana, who possesses the body of a young man. A few bravehearts will go out of their way to find who that woman is and what she wants to leave them in peace.

What I appreciated most in Su from So is the clever transformation that takes place in the realm of genre: from a horror comedy to a village comedy. The jump scares, the spine-chilling fables, and the ominous music score are all there, like you would find them in any Stree or Bedhiya franchise movie. But in place of expensive, dazzling VFX we get colorful but hastily tied dhotis; instead of ethereal, otherworldly women seducing simple-minded youths, we get middle-aged, grey-haired spinsters revving their romance with pot-bellied left-over village men. What binds these two different worlds together is the slapstick comedy and the one-liners; and there are plenty here. This spin on genre expectations is helping to ground the movie to a familiar reality, while lovingly beckoning to the tropes of horror comedy, a highly popular genre in mainstream Indian cinema right now, in Hindi and other regional languages.

The sometimes frustrating and sad everyday facts of rural life are realistically but heartwarmingly portrayed. The peculiarities of odd characters, like the drunkard and his all-endearing wife, the good-for-nothing youth and their hard-to-get girls, the village blowhard, contribute to the development of the story without falling victim to silly laughs. Facets of village mentality, like the easy spread of unverified rumours, superstitiousness and belief in tele-evangelists, become key plot points. The strict gender roles and the overwhelming presence of men in public life are part of the visual language of the film, clearly seen on screen. The movie is dominated by its male characters with only exception of the ghost that overtakes their lives, and her (still living) daughter who brings closure to the story.

What struck me in particular was the use of the music and the background score: the heavy electronic music is a mismatch to the rural, rustic setting on screen. I think the creators pursued this apparent contradiction to invite the audience to see the characters through modern lenses, not as leftovers of the forgotten past of the village, but as dynamic protagonists of our present.

The only criticism I had leaving the cinema hall was the closure. Violence against women always disturbs me, but the makers found it necessary, even to this day, to use that angle and portray it bluntly on screen. I believe they did that to justify the necessary final fight scene and wrap up the film like a proper southern entertainer. Why? It did the job perfectly well as a comedy of errors. Fortunately, by the time of writing this post, those parts have faded from my memory, and I am left with the sweet and spicy aftertaste of a joyous film.