A complicated nexus of forbidden lovers, bloody family feuds and unchecked power-hungry royals, Rajput’s plot is difficult to keep up with. Still, I will try my best: Janki is in love with Manu, but they belong to warring families, so their love is impossible. Bhanu, Manu’s brother, is in love with orphan girl Kamli, but she is raped and gets pregnant by Jaipal Singh, the deposed royal of the region who still treats the villagers like his property. Therefore, Bhanu’s love with Kamli is impossible. Then Dhirendra, a policeman and Janki’s childhood friend, also falls in love with her, but she doesn’t, so his love is also impossible, but he marries her anyway… Things get serious when during Janki’s marriage procession, she is attacked by goons, and Manu kills one of them when he attempts to rape her. But since Dhiren is a policeman and present at the murder, Manu goes to jail in an effort to save Janki’s reputation (who is already pregnant with Manu’s child). But the goon who Manu killed was a relative of the deposed royal Jaipal, who seeks revenge by killing Manu’s father. Subsequently, Bhanu becomes Bhavvani, a dacoit, to avenge their father’s death. So that’s how the film ends up in daku territory, although it’s more of a feudal drama kind of story.

Rajput is directed by Vijay Anand, the director of gems in Hindi cinema; some of the titles include Guide (1965), Teesri Manzil (1966), and Jewel Thief (1967). Also, Dharmendra and Vinod Khanna come together again for another Dacoit movie after Raj Khosla’s Mera Gaon Mera Desh, which I wrote about in an earlier post. But the surprise here is Rajesh Khanna, the romantic hero, has turned serious in this one, chasing hardened rebels, but he still retains his lover / sacrificial persona when he romances Janki even when she has clearly given her heart to another man.

The circle of the dacoit’s rise and fall

In most dacoit films, it is important to explain the motives behind becoming a dacoit. The exceptions are the curry westerns, like “Sholay” or “Mera Gaon Mera Desh” where the dacoit is a primordial villain with no justification other than his indulgence in cruelty. Rajput, though, falls into the category of the older dacoit film, the noble rebel, like “Jish Desh Men Ganga Behti Hai” and “Gunga Jumna”.

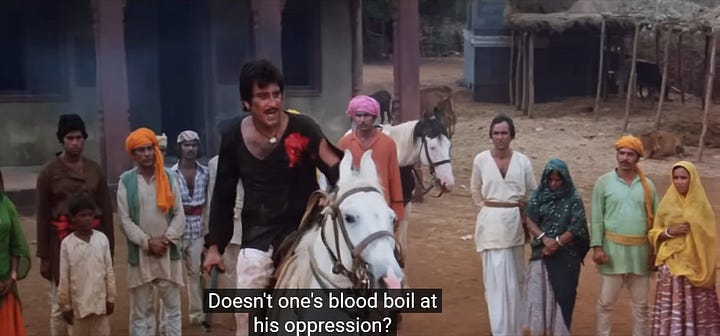

The raison d'être for the rise of Bhavvani the dacoit is his fight against the unjust hereditary, feudal power that suppresses the common folk, which becomes one of the movie’s major themes. Often, the dacoit film explains the whole circle of the rise and fall of the dacoit, how someone becomes a dacoit, and how seizes to be one. Rajput also employs this narrative structure in a straightforward and clear-cut manner. The scene in the first half, close to the interval, where Bhanu turns into Bhavani, the dacoit, is the most pertinent in our discussion. Time-wise, the scene’s placement in the movie’s runtime, agrees with many other dacoit transformations near the interval. Here, Bhanu showcases how dacoits, who are rebels, not criminals, are born. First, Bhanu on top of a horse and towering above the rest of the villagers, reminds them of the great injustices they suffered from the royals. Then, he appeals to their sense of honor and asks them how can they remain indifferent to what is done to them. Next, he asks them to join him in resistance. And finally, the villagers, one by one, join him in his noble cause.

But when eventually that common folk try to get rid of their tormentors, the cops come… and the rebels have to submit to state authority for the good of the country. The message here is that, ultimately, dacoits have to be engulfed back into civil society.

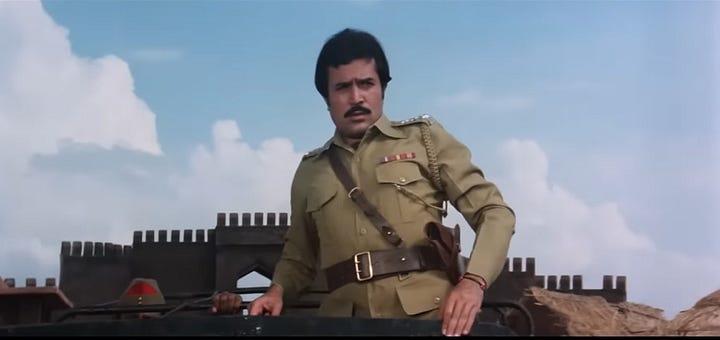

In cinema language, the movie relays this message with a scene that is so well articulated to what it wants to communicate that I was struck with awe the first time I saw it. It’s a typical scene of dacoits surrendering to the police but I consider it essential in understanding what dacoit films are about, as a genre. The dacoits, after a party among their people, are visited by the police in a jeep. The policeman in the jeep is shown at a low angle, towering above the walls of the rebels’ town, meaning he is in control of them. Then, he speaks above them while standing straight on his jeep and the poor dacoit folk watch him from the ground level. Their conversations continue for the majority of the scene in these positions, effectively underlying the superior power the police hold over (literally and metaphorically) them. The whole scene is shot in a mounting crescendo of arguments and counterarguments, with side characters intervening in the process, like an ancient Greek Choros taken from a tragedy play. Eventually, the dacoits surrender their guns to the police, signaling their submission to the state.

In contrast to the ending of Kucche Dhaage, which I love because the dacoits there oppose the police forces until they are murdered, here they make a pact with them instead, because they are very understanding about how society cannot function in a constant state of violence between groups, so they decide that they will be the party to step down. Of course, by doing this, they surrender their ability to inflict violence to the state and the state thus becomes the sole monopolizer of violence. In this way, the movie reaffirms the claims of the modern (bourgeois, neo-liberal, call it how you like it) state to exclusive violence.

Should you watch it?

I love watching dacoit films but… the eighties were truly a no man’s land for Hindi films… Here you have a distinguished director, a cast consisting of legends like Dharmendra and Hema Malini, heartthrobs like Vinod Khanna and Rajesh Khanna, pressing social issues and valuable messaging - the right of the people to rebel against unchecked authority, the importance of inclusion of dissenting voices in the body politic etc. But alas! The need for cheap thrills translates to complicated relationships to generate over-the-top melodrama, sexual titillation disguised as social consciousness through the repeated depiction of rape, and endless fights make this movie a bit of a drag… And seriously, what is it with the rapes? The first rape occurs within the first half of an hour and an umpteen number of rapes follows. Women seem to exist just to be raped!

But I don’t want to trash the film because I did enjoy watching it especially the 2nd and 3rd time. It really grows on you with repeated viewings; once you solve the riddle of the complicated relationships and power struggles, you have the time to relax and enjoy the cinematography that brings out the beauty of locations, and the richness of settings and costumes. The songs are also part of my repeat playlist as well. My favorite is “Doli Ho Doli” where the bride Janki is taken away in a palanquin:

You can watch Rajput on YouTube with English subtitles: